Cathedral of Mars

My grandfather was an author of some 200 short stories. He was published in The Saturday Evening Post, Esquire, Playboy, and various SF compendiums alongside Alfred Hitchcock and Carl Sagan. He was looking to earn more respect for the Science Fiction genre long before it was a major industry, using his stories to warn about post-war government overreach and nuclear power.

But to me, he was the old war hero who kept to his tiny garden and his tinier office, listening to a Napa police scanner, preferring an old Royal typewriter to the suspect telephone.

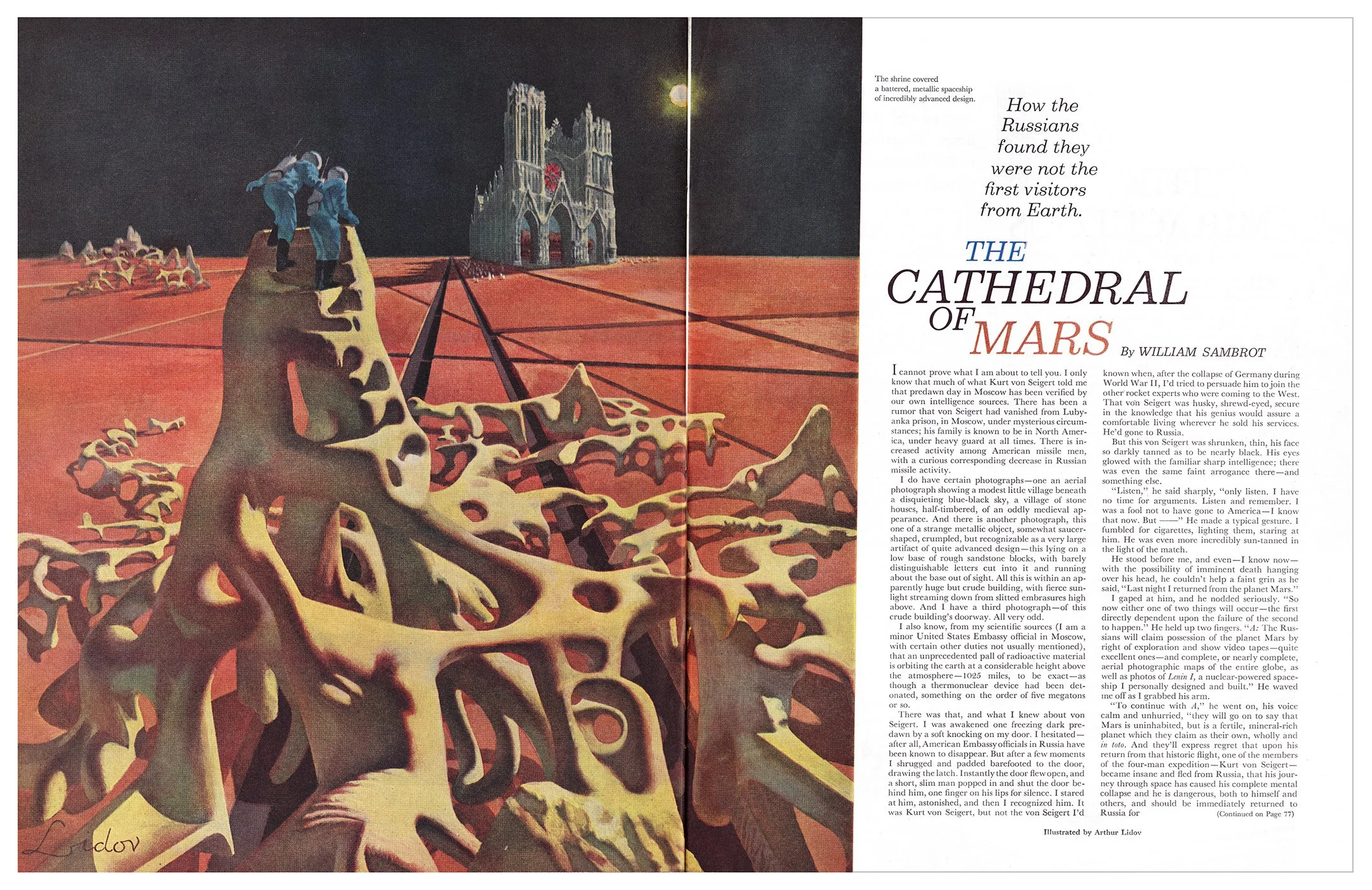

Over his desk hung a painting by Arthur Lidov which had accompanied his story “The Cathedral on Mars,” and appeared in the Post on June 24, 1961. It depicted two astronauts summiting a skeletal mountain on Mars, stunned by the unthinkable sight of an earthly Cathedral.

William was so taken by the illustration that he wrote Lidov to compliment him. A short while later the original painting arrived by mail, which he proudly framed.

I was transfixed by it.

It said so much, so forcefully, with so few visual devices. How did the Cathedral get there? What was inside? You had to read to find out — to go inside.

This was my first peek into the editorial world: the duet of writing and image, the dynamics between authors and illustrators, and eventually, the alliance between strategy and identity.

More than any of his possessions, that painting stayed with me. It suggested something subtle but powerful: illustration does not compete with writing — it funnels people into it. It collapses distance. It creates entry. It makes the abstract tangible.

It was the first time I understood how ideas travel: illustration reduced the noise and amplified the signal.

I wanted to sign on for that.

Writing, I assumed, was taken. That was my grandfather’s territory. His discipline. His voice — hard earned.

So I moved sideways.

I sketched. I composed. I structured meaning visually. I learned how to imply narrative without stating it. I convinced myself that image was enough — that someone else would handle the words. My job was to get readers to them.

So I did.

I followed internships. I wedged my way into small periodicals. I focused less on cultivating a definitive style and more on consistency in how I thought and worked. In the pre–digital era, my name began to bubble up.

Soon I was doing work for publications my parents revered — ones even William might have been proud of. That mattered more than I expected. Things felt like they were falling into place.

And then...it all melted away.

Phase Change

By 2010, most freelance editorial work had dried up.

Illustration as a storytelling device wasn’t disappearing — but it wasn’t paying. Not on the page. And the page was part of the ritual: walking down to the local cigar and magazine stand, buying my copy, smelling the ink — the rock-solid signal that the job was done. In some ways, that moment felt more valuable than the check.

Major publications were moving online or folding. What had once been a viable path narrowed almost overnight.

I was witnessing what was being called “The Death of Print.” At the time, it felt like career death.

“Digital transformation” was being batted around as a term, but no one knew what it meant — or how to get it done. What I did know was this: translating dense information into visual language was useful, and I was good at it. But it took time to connect that ability squarely to brand and identity. The tools were the same. The context had changed.

Editorial had taught me how to synthesize narrative, hierarchy, tone, and timing. Brand demanded that I apply those skills at scale, under constraint, and in collaboration with business.

The question wasn’t whether I loved illustration.

The question was whether I wanted to own a craft, or translate meaning wherever it was needed.

Creative Migration

My grandfather spent his life fighting for authorship: for recognition, for legitimacy in a genre that had none in his era. He held tightly to what he made. He earned the right to die on the hill of ownership.

I entered a different world. One where ownership is diffuse; where creative output lives inside systems, and no single person can claim authorship once money and scale are involved.

In this world, what skill remains liquid — exchangeable across tectonic shifts in culture and work?

Translation.

Editorial trained me to solve problems with clarity. Brand required me to solve them collectively.

That shift — from craft to translation — is what moved me toward leadership.

The core skill wasn’t illustration. It was synthesis. The medium changed. The responsibility expanded.

In translating complex ideas into visual invitations, I began to sense something more durable than the craft itself.

Branding, yes — but more importantly, leadership. Helping companies and people navigate market shifts — especially when what they are good at is suddenly redefined, or just disappears.

What remains is how we think. How we solve problems.

And here we are again at another nexus of change with the arrival of AI — another force that appears to threaten the value of the work we care about.

But AI does not erase talent. It exposes positioning. It forces clarity.

The “Cathedral of Craft” — visual design, illustration, artistry — may crumble. But deeper within are chambers where the real work happens: process, judgment, translation.

Just as I migrated from illustration to brand, and then to creative direction, many people will need to relocate themselves in the market. Creative careers are no longer linear. They are migratory.

Clear leadership eases these changes. It clarifies what good thinking looks like. It protects meaning, even as mediums slide around.

What remains valuable are people who can translate volatility into durable systems.

What Endures

I still picture that Cathedral on Mars: my grandfather describing it, Lidov seeing it.

Two explorers crest a summit and find something ancient, improbable, and sacred in a place that shouldn’t contain it. The image works because it collapses disbelief into curiosity. It invites you forward — into the story, through the arches.

I rescued the painting from my grandfather’s house after he passed. Years later, I lost it in one of my own moves. Now it exists only in memory — something I have to reconstruct not just visually, but emotionally. What it felt like to stand in its presence. What it did to me.

Leadership feels similar.

You arrive at a landscape that looks barren — a collapsing industry, a volatile market, a shifting platform — and you’re asked to make something coherent there. Something that can hold belief. Then the scenery changes again. The artifact disappears. Only the memory of what mattered remains.

Editorial taught me how to make people lean in. Brand taught me how to align that instinct with business reality.

Leadership asks you to do both without clinging to a medium. What lasts is not the format. It’s the ability to translate meaning across formats.

What makes for a long and healthy career is not passion for a tool, but fluency across terrain.

The work relocates. Platforms shift. Craft evolves.

You move with it — or you become attached to something that no longer exists.

For me, leadership meant stepping away from granular design and toward meaning.

It isn’t about protecting a medium. It’s about protecting meaning — and making new mediums legible. In an era of infinite output, the scarce skill is discernment: knowing what deserves attention, and what doesn’t.

And rarer still: the ability to help others navigate as the terrain keeps shifting.